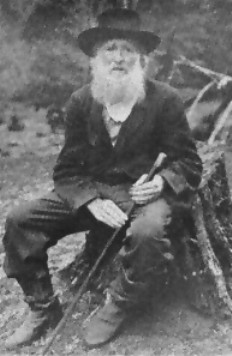

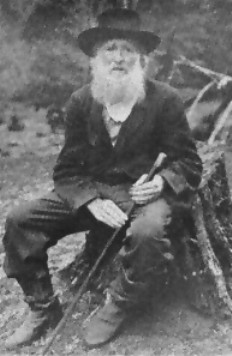

UNCLE BILLIE'S STORY

William Boykin Killough

"Uncle Billie"

UNCLE BILLIE'S STORY

William Boykin Killough

"Uncle Billie"

Many of those checking out this site know the general story of the 1838 Massacre that was of common interest of Killough descendants all over the country. All the details known of this event are written in William B. Killough's own handwriting or recorded as his own spoken words. This record has been filed in the Archives of Texas at Austin. It's original publication is in the book "Larissa", a collection of records of the lives of early pioneers in the area of what is now Cherokee County, Texas. They were diligently researched and recorded by Fred Hugo Ford, D. D., and J. L. Brown over several years. The exact date of publication is not written in the book. The following is quoted verbatim , including punctuation, from that book.

Seated amid the dim ruins of what had once been his father's home, William B. Killough, the child of the massacre, eighty years after the tragedy, recited with tremulous voice and copious flow of tears, the story of his escape as it had been repeated to him again and again by his mother, Mrs. Narcis Killough, an eye witness to the tragedy.

Mr. J. L. Brown, W. Y. Forrest and myself visited the home of Mr. W. F. Partlow, son-in-law of Uncle Billie Killough, with whom he lived in his declining years. On this visit Uncle Billie promised us a manuscript containing the story of the Killough Massacre as he had often heard it recited by his mother earlier in life. Two days later he sent it to us by Mr. Partlow. This story, written on foolscap paper, yellow with age, rolled and tied with ordinary spool thread, had been prepared by him in his more vigorous days and had been carefully preserved in his trunk for more than thirty years."I was born in Montersville, Talladega County, State of Alabama, in the month of September, 26th day, 1837. Father moved to Texas the same year, stopping where old Larissa now stands, the 24th day of December 1837, it being some forty miles from any white settlement, Lacy's Fort being the nearest. They built houses, cleared land and made a crop. Everything went well until the fall of 1838, when the Indians began to give trouble.

The Killoughs, together with the families of O. C. Williams and George W. Wood, left, but on making a treaty with the Indians, they returned to gather their crops and stock. They had finished all except about two hauls in Uncle Nathaniel Killough's corn. As they would not be out long, they decided to leave their guns at home. (They had been in the habit of taking them and stacking them in the field.) About one o'clock, they started to the field. On their way, the larger potion had to cross a creek. In passing through the swamp, they were attacked by the Indians and all killed, xcept Nathaniel Killough, his wife and child. He was watering his horse. (He lived on that side of the creek.) On hearing the firing, he rode to the house and tried to get is wife and child upon the horse, but the Indians pushed him so he had to leave the horse and take to the cane. He made his way to a friendly Indian and got another horse and made their escape to the Fort. The baby girl, which was about one year old, is still living. She is the wife of C. W. Matthews, of Garden Valley, Smith County.

Samuel Killough, my father, lived on the Northeast side of the creek. When mother (Narcis) heard him firing, she took me up and started to see who was killed. She was joined by Aunt Jane, Isaac Killough's (Junior) wife, and her brother, William, he taking me to carry, for mother was very weakly, (stationary weight being 94 pounds.) They did not go but a few steps when they saw the Indians coming. Handing me to mother, Uncle William said, "Here's the baby, I must go." The Indians swept y the women and shot Uncle William down a few yards from them. They found father in a small branch beyond the main creek, where he fell. The balance they failed to find, except grandfather, Isaac Killough, Sr., he was lying in his yard and grandmother was all alone.

In this massacre there were eighteen killed and taken off. Wood, a brother-in-law of the Killoughs, his wife, five children, a Miss Williams, a sister to the young Williams, spoken of, a Miss Killough, sister to father, were all taken off and were never heard of. The girl was about seventeen years old. Williams and Miss Killough were to have been married soon.

After trying to get grandfather in the house and failing (he being very large) they covered him up with quilts, laying rails on the sides to hold them down. They turned their steps to the East. Returning to father, they found everything torn up and strewn over the yard.

After some time taken up in consultation, (there being three women) Mrs. Urcey Killough, Jr., Narcissa Killough, wife of Samuel Killough (my mother), the Indians sent for them while they were at the house to go to Sam Bengs, their Chief, about two miles North. The first two mentioned were in favor of going. Narcissa Killough told them they could go, but she would die first. So one of the three Indians sent for them (Dog Shoot by name) told them if he had a gun he would kill them. (The male portion being dead, the Indians did not bring their guns.) Narcissa sent them for their guns, and while they were gone, she took the baby boy up and started on their long journey of forty miles, without anything to eat, among savages and wild beasts. They hid in the grass, near where Larissa now stands, until night came. They could hear the Indians yelling and see the smoke from the house, which on returning, and not finding the women, they set on fire. When night came, the women started for Lacy's Fort, traveling as best they could, as they had to leave the path often on account of Indians coming up all through the night. There was one serious drawback to them, one that might have proven fatal to them at any time. They had an infant one year old and a small fice dog along. The cry on one or the bark of the other would have been fatal, but it seems that both knew there was something wrong for, when they would stop, the dog would hover under their skirts like he was trying to keep out of danger. In starting, they didn't know what to do with the dog, they could not leave it, and didn't have the heart to kill it, nor anything to kill it with.

The third day, in the morning, as they had been without anything to eat, they concluded they should travel by day, (they had been hiding in the day-time) they had not gone far, when they heard a noise behind them; they turned and there was an Indian with his gun to his shoulder ready to shoot. As some of the women screamed, he ran up and showed them there was no powder in the pan (all guns were flint and steel then.) The path forked at that place and the Indian wanted them to turn to the left, a dimmer path; they refused to at first. (He could not speak English and had to use signs.) As they would not go, he got in the trail ahead of them and leaded his gun. They concluded it was death anyway, so started his way. They had no gone far before they came to an Indian hut and about two hundred Indians painted. They were killing a beef. They were carried to the hut and put in, the same Indian sitting in the door holding a gun. A negro woman came in; mother asked her some questions; she gave no satisfactory answer. They gave them something to eat, the first they had had in forty-eight hours. They sent off for an interpreter, and when he came, he told them they were safe. Had the women gone one-half mile further, we would all have been killed, as the Indians in the town ahead were on the warpath. That is where the painted ones were from.

He also told them the Whites had a great many friends among them, and they knew that there were three women trying to make their escape and they had placed guards all over the county to find them, if possible, but as they had traveled by night, they had not found them before. They were kept there until the next morning, when they were furnished horses and sent to the Fort. The Indian who captured them, rolled up in his blanket before, and laid across the door all night.

This place is about four miles West of where Rusk now stands. They came very near being shot at the Fort, as it was night when they reached there, and all ere excited. They were hailed three times, finally they answered "Women from Saline," just in time to save themselves.

There was an amusing incident that happened while we were in the Fort. One day it was reported the Indians were coming. Mrs. Box got Johnny Box, her husband, down and began to beat on him, saying at the top of her voice, "Pray, Johnny Box, do pray, if you ever did pray, pray now, for the Indians are coming."

We stayed in the Fort about a month, then went to old Douglas; then mother and I soon left for Alabama.

Will stated that there were Whites with the Indians in the killing of our family. There was one by the name of Hawkins, from Talladega County, Alabama, that my family knew. In about five weeks after the Killoughs were killed, General Houston sent General Rusk up and drove the Indians back and buried the dead. Uncle Nathaniel Killough was with them. He was wounded in the Kickapoo fight, being shot through the shoulder.

Verbal supplement by William B. Killough to Story of the Killough Massacre"The tragedy reported at Lacy's Fort, a detachment of soldiers, guided by Nathaniel Killough to the scene, came and gathered up the remains of the murdered men and buried them in the forest under a great oak, since fallen, a few hundred yards east of the old Samuel Killough home. The picture [not available here] shows the rough stone markers where their remains repose.

General Thomas J. Rusk accompanied the party to the scene. It was believed by survivors of the tragedy that the raid was inspired by a white man whose name was Hawkins; that such a man had earlier joined the tribes and occupied prominence among them. As Mrs. Narcissus Killough was about to make her escape a raider approached her, giving her the assurance that they would not harm the women and children. She could, through the paint and garb of the Indian, discern the unmistakable marks of a white man, and upon his recognition, he turned and rode away. Hawkins, who was not known as a white man in the fight, was the first to return to the old settlement in Alabama and to report the tragedy.

My mother, Mrs. Narcissus Killough, escaped with me and returned to Alabama the same year. We went back to Larissa in 1851, and later made two trips to Alabama, in 1853 and again in 1855—returning finally to Larissa in 1856.

My mother, who afterwards became Mrs. John Sammons, died in 1881 and is buried at Larissa. After the raid the Indians ransacked the premises, ripping open beds and turning everything upside down, apparently in search of treasure.

The old Samuel Killough house was fired, but only a portion burned away, owing to green timbers or rain. It was later repaired by Nathaniel Killough, who resided there during many subsequent years."

The subjoined extract from the petition of Nathaniel Killough to the Texas Congress in 1836, will give his account of the names of the persons killed or captured in this tragedy.

The most notable event in the annals of Indian depredations in Cherokee County is the murder of the family and relative of Isaac Killough, which took place near where the old town of Larissa afterward flourished. Some fix the date as in the Fall of 1837, but the subjoined statement of Nathaniel Killough seems to fix it on October 5, 1838.

Having settled there in 1837, and having planted crops, owing to the threatening conduct of Indians and Mexicans, the family moved back to Nacogoches; but in the Fall they ventured back to see if their crops were undisturbed, and to gather what they could find of them.Then returning from their fields at noon on the 5th day of October—be it 1837 or 1838—they were fired on from ambush, and several were killed.

Allen Killough, his wife and five children were never accounted for, and it is not know how many were taken into captivity nor how many of them were killed. Neither were Miss Elizabeth Williams nor Miss Killough ever heard of again. It is said that a son of Mr. Wood was adopted by the tribe, and finally became its chief.

Following is the petition of Nathaniel Killough to the Texas Congress in December, 1838:The petition of Nathaniel Killough humbly showeth unto your honorable body that he is now, and has been for some time past, a citizen of Nacodoches county; that during the past Summer, petitioner, together with his father, Isaac Killough; his brothers, Allen Killough, Samuel Killough and Isaac Killough, Jr, and his brothers-in-law, George W. Wood and Owen C. Williams, resided near the Neches River, in said County, and were at that time engaged in the pursuit of agriculture, and that at their residences they were, on the 5th day of October, last, attacked by Mexicans and wild Indians; and that Isaac Killough, Sr., Allen Killough, his wife and two children; Samuel Killough, a daughter of Owen C. Williams, and Elizabeth Killough, were killed, as your petitioner believes.

Your petitioner would also show unto your honorable body that at the time his relations were murdered, Mexicans and Indians took and destroyed all the property of your petitioner and his relatives; and that the property of your petitioner so destroyed consisted of household furniture, farming utensils and arms of value of $2,000; 500 bushels of corn, worth $1,000;a carriage, worth $200; a wagon, worth $250, two horses, one of great value, both worth $700 a wagon, worth $150; the entire loss of your petitioner being $4,300; and that Isaac Killough, Sr., lost property of the same description of the value of $2,500; and that Allen Killough lost $3,800; Samuel Killough lost property worth $3,700; Isaac Killough, Jr., lost property worth $700; George C. Wood had property destroyed worth $2,400; and that Owen C. Williams lost property worth $2,300; and the value of the property before mentioned has been entirely lost to your petitioner, and to the heirs of his relatives; and that every possible effort has been used by your petitioner to recover the property mentioned, but that you petitioner has been unable to recover any of said property.

In consideration of the premises, your petitioner prays that your honorable body will grant to him and Owen C. Williams and the heirs of Isaac Killough, Sr., Allen Killough, Samuel Killough, Isaac Killough, Jr., and George C. Wood, such relief as a sense of justice may dictate; and that your honorable body will duly consider the prayer of your petitioner; and that your petitioner, as in duty bound, will ever pray.

Nathaniel Killough

Nacogdoches, Dec. 26, 1838

We, the undersigned citizens of Nacogdoches County, respectfully represent unto the Honorable Congress of the Republic that we have examined the foregoing petition of Nathaniel Killough, and that we are satisfied the statements made in the foregoing petition are true, and we pray that the honorable Congress will grant the prayer of the petitioner.

Signed by R. H. Finney, Osc. Engledon, Jas. H. Starr, Wm. Hart, D. Ruck, K. H. Douglas, M. M. Cox, Henry M. Rogers, Jas. S. Linn, J. Smith, Chas. H. Taylor.

Eliza J. and William B. Killough